This interview was originally published through Audible Sessions.

Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

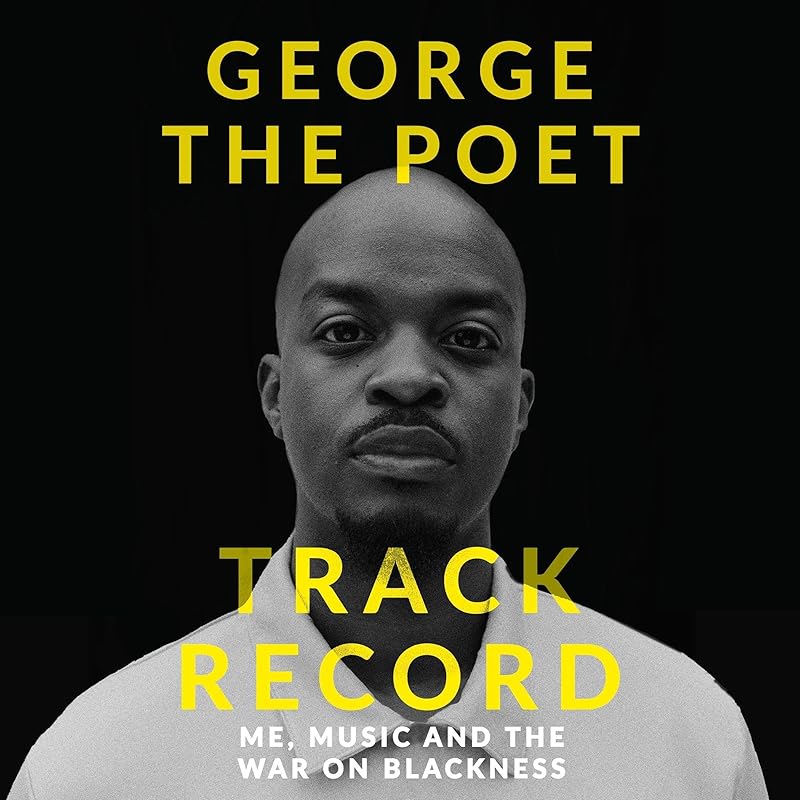

Holly Newson: I'm Holly Newson. Welcome to Audible Sessions, a place where we delve into the books, careers and lives of authors and creators. George the Poet is a podcasting sensation. His podcast Have You Heard George's Podcast? had everyone answering yes. And it was such a huge success in large part because of his poetry, which he created off the back of making grime music. Since then, George has been working on a PhD and writing his book, Track Record. It's a book that merges memoir with an examination of capitalism, imperialism and more, not your everyday mashup. And it's also a book that was a long time in the making. So, I started by asking George why it took so long for this book to come to life.

George the Poet: The short answer is, I changed. Writing the book changed me. And I was writing from a different vantage point by the end of it from that which I started with.

HN: What was that change in you?

GP: I think fundamentally I started from quite an individualistic place. I was happy to just explain my story and what it indicates to me about the world, but my story just seemed to be less and less important in the context of other things that I was learning.

HN: And what the book became, why was that the book that you felt was the right thing to put out there?

GP: Well, I think my intention of explaining some things about the world through my life experience was not completely misguided. I think that was a worthwhile thing to do. My work has followed that pattern for a while, and at the start of my poetry, I did that in a particular way. I talked about what I experienced in my neighbourhood and how that influenced my approach to rap music and academia and community. But by this point in my life, I'm looking at much more global forces, and these forces are accelerating. They aim to be all-encompassing, and they affect damn near all of us. I can't think of many areas of life that are untouched by some of the forces I talk about in the book. Neoliberalism, imperialism. So, the book had to be reflective of that learning.

HN: One of the things that comes up a lot in the book is capitalism and our capitalist systems. So, why do you say that they are rooted in racism, those capitalist systems?

GP: I think at the onset of this new mode of exchange and production, what we now call capitalism, there was a racializing, there was a need to create a group of people that were beneath the capitalist people that were said to be biologically, irrevocably, irreversibly, irredeemably inferior. And it started off with the peasantry of England. I mean, one way to read the history of capitalist development is the peasantry of England being othered and being forced to become landless workers that branched out into the Irish. The way the English treated the Irish became the way the West ended up treating the non-white world. And it still very much is the function of these groups is to drive production without impinging, without encroaching on ownership, like there is a class that is supposed to own and profit from production, and there are masses that are supposed to just give their lives, their land, their time, their children to that process. And that is an inherently racial construct.

HN: A lot of the book is also about music. And you write the music business is a really good example of how capitalism in the world works. So, why is that?

GP: Right. At the risk of preempting my PhD. I'm trying not to step on my PhD's toes. Music is amazing. Music is boundaryless. Music travels and music is an amalgam of all of our experiences. So, when you start to delineate these experiences, you start to dive into where these musical influences come from, the conditions under which they emerged, and then the ways that they were commercialised. Yeah, you can get quite a good glimpse into how global capital works or how the production, the labour, the life experience that goes into creating music is alienated from the profit. You know, they're just communities, populations, literally dying to produce a lot of what we know as Black music, generation after generation under different contexts of oppression and tragedy and exploitation, expropriation from Jamaica to Congo to African America. And a lot of the time – in fact, every time – the overall condition of the group that produces this music is just completely not reflected in the commercial ascent of said music.

HN: You write that Jay-Z is not really a self-made man, that no one can really be a self-made person. So, why in that particular example, let's take Jay-Z, would you say that he's not a self-made man?

GP: Well, yeah. No one is really self-made. Jay-Z is not self-made in the sense that he didn't emerge out of nothing. It's become very common to characterise hip-hop as something that started out of nothing when actually it started out of communities that had collective practices. Again, not to preempt my PhD, because I am doing a lot of, I'm trying to perfect and refine a lot of the definition of what I'm talking about. But, yeah, ultimately, these communities have production processes that allow them to process the world in a certain way and using storytelling techniques that become increasingly specific to their context.

So, what that means is that this community is uniquely responsible for the music it creates. It's not to say that Jay-Z dropped anywhere in the world with the same biology but just a different context would still be the most prominent, probably the richest rapper in the world. No, probably not. If he was born in Congo, if he was the same person with the same parentage, even, in a different city at that point – he was born end of 1969 – it would be different. And yeah, it's become taken for granted that the self-made man is at the core of hip-hop, which is a great snapshot of capitalist propaganda.

HN: What did your own time with a record deal teach you about the music industry?

GP: My time in a record deal revealed to me that, as I put it in the book, not all assets are created equal. So, the idea of a record deal is that talent needs funding, as everything does. A lot of the time artists are berated for signing record deals because they are being said to over-rely on an industry, on white capital and, you know, but let's be honest, in order to scale anything, it takes investment. So, you are bringing your talent and they're bringing the investment, but ultimately, the investment, the financial capital, gets the final say. They get control of the budget, therefore they get to decide what to amplify and what to mute. And I felt that that was part of my education in that record deal.

HN: What were they muting of you?

GP: Some of my more thoughtful strategies, some of my more thoughtful material. People often said lazily to me, which is just a truism that pervades a lot of mainstream Black production processes, audiences are not interested in thoughtful stuff. Conscious stuff isn't as appealing as non-conscious stuff. But I always went to great lengths to try and satisfy what I was reading from the market with what I believed was in the best interest of the consumer of the community.

So, I would, for example, make my first EP all about the start of a traumatic family, how a problematic relationship becomes a problematic family structure. And some of my framing was problematic. Some of my work was, you know, I look back on it and think I would approach that slightly differently. However, the intention was to support and to facilitate healing, important conversations about the way we view each other in romantic situations and sexual situations, and how that becomes a brand-new life that now is fraught with problems. And I had a whole strategy. I wanted to place this body of work in mother and baby shelters across the country. I felt like that was a good idea, but it was just ignored for longer than I found acceptable. Yet when I produced what you might call lowest common denominator music, everyone acted like I had reinvented the world. Everyone was like amazed at my genius. And I'm like, “Oh my God, this is the emperor's new clothes.”

HN: So, you left that music deal and you ended up leaning more into poetry. But how did the poetry begin? When was your first step into the music becoming poetry?

GP: I always conceptualised our early rap under the era of grime, first-wave UK grime music, I conceptualised that as poetry. We put a lot of effort into making sure our words were as artistic as possible. I found in grime the allowance of what we could talk about restrictive, what we were encouraged, again, by the market, and again, by our peers absorbing these market indicators, these norms that we saw from the mainstream. So, my peers would say to me, you know, you can't talk about what I wanted to talk about – my reality, studying, being concerned for my community, trying to forge a part of manhood, masculinity, Blackness. That was not toxic, was not self-destructive, didn't start from all the negative assumptions about our nature that hip-hop and grime was promoting. But yeah, my peers would be the ones to intervene and be like, "Hey, man, this isn't gonna work."

And I was always of the opinion that we don't have enough of a sample to say. Like, who's trying? Who's attempting, to allow us to assess their performance? And interestingly, I was able to separate myself from the fray. I was able to stand out over time, and that was from taking the same material that I was making as a grime artist and delivering it differently, which became poetry.

HN: And you write about your time at Cambridge University and one moment where a fellow student asked if you'd perform grime, and you didn't feel comfortable doing that in that environment. So, what was your thought process then when you thought, “I don't feel okay with this. What else could I do?”

GP: You know what, it's complicated every time I think about it. Because there was an element of self-consciousness. I'm like 19 years old. I've come from a very Black community, a very mixed, even though it was a selective grammar school, it was very mixed. The biggest ethnic group was probably South and East Asian. That was my context. And then, I mean, Cambridge, where there's not that many non-white people, which in itself isn't the be all and end all, but it was indicative of a class environment in which many people didn't relate to my context.

So, I was very self-conscious about how that context is presented. And I understood grime music to be quite fast-paced. So, if I'm going to be performing high-octane, fast-paced music to an audience that is not familiar with my cultural context, I might end up looking like a caricature. And that frightened me. That made me just say, “I'm not gonna perform. I'm not gonna present my artistic side in Cambridge.” And eventually my friend that pushed for this, I compromised with him and said, "Look, I'll perform, but it's not gonna be how you remember me performing."

HN: And there's one thing you wrote in the book about when you were at Cambridge, you became kind of more isolated, more introverted, and that that's something that never really fully left you. Is that something that you still feel now?

GP: Yeah, yeah. I find a lot of intersecting influences that I do think that celebrity can be an alienating experience, but also I feel that there's something about London in particular, maybe Western Europe, maybe Western society in general. It leads us to form very atomised lives where it's just harder. It's a lot more effort to stay connected. But then also, returning to racial capitalism, I found that the further I progress in my career, the harder it is to find people of my ilk, of my walk of life in the professional spaces where I'm spending most of my time. And all of these things come together to make me a bit of a loner.

HN: Do you miss that kind of community from school where it's kind of a moment where you are kind of pushed into it?

GP: Yeah, I do miss it. I always think about how different my experience of this country would be if the people I grew up with all had the same access to opportunities as I did, and were not now being increasingly, I'll be honest with you, increasingly consumed with the mental health, the deteriorating mental health implications of poverty, unemployment. Those are the main things. I'll leave crime out of it because crime is not as big of a factor as poverty and unemployment in the disintegration of my community.

HN: So, what things do you do to kind of feel like you are still part of community?

GP: The main thing, I guess, is paying more attention to my actual family and friends. I hint at this in my transition to podcasting that I write about in the book, where just listening to my nephews a little bit more, being on the ground in Uganda, unfortunately, in the prison system, it will connect me more directly with the community that I grew up in. The music scene as well, it remains a connector. And a lot of what I'm describing is also juggling the transition into different stages of adulthood, because the older you get, the less leisure time, the less communal time that you have. So, it becomes more important to give of yourself to your loved ones, your friends, and in my case, your audience.

HN: And you mentioned Uganda there. You went for a good trip there before you started university. What did that trip and that time in Uganda mean to you?

GP: That time in Uganda allowed me to experience being an African in Africa as a young adult. Really, really nothing like it. The older I get, the more I realise it also gave me the basics of a Third World perspective. There are elements of the Global South experience which are quite consistent across what used to identify itself as the Third World. I know that's become an awkward phrase, but as I explain in the book, it actually stems from the identification of those emerging from colonisation, as not necessarily aligning with capitalism or socialism, just being the undecided third estate, in French parlance. Yeah, so looking at the world through that lens allowed me to think more critically about our experience, firstly in Black Britain, then in Britain, then in the West more generally.

HN: And do you think that that was something that clicked for you straightaway? Or was that, because you mentioned earlier your mindset has changed a lot, the way you think about things has changed. Did that click straightaway? Or is that something that you can see easier in hindsight?

GP: I think there are some things that click straightaway. And it occurred to me that in Uganda, I am not Black. No one ever dealt with me as a Black person. I'm not the first writer from the diaspora to return to Africa and experience that revelation. Many people have talked about it before me. But for me, that was stark, especially coming from a year, as I mentioned I think in the book, a year in which London was experiencing its worst wave of teen violence in a long time. I did feel that there was something toxic happening among my demographic, which I still see among young people of colour in this city in that age bracket. There's a fear, there's some real disturbing things happening to an alienated mass of young people in this country. Uganda provided a breakaway from that, and it was very obvious.

But yeah, over time, having to think more about the things that characterise a typical Global South economy in terms of its susceptibility to imperialist manipulation, the function of what is called democracy, how that actually works within the global context and why it is laundered, its image is laundered in the way that it is. Those things take quite a while to wrap your head around.

HN: And so how does the West continue to disrupt African countries long after colonisation is supposedly over?

GP: I think it's very important to understand that what we're told about capitalism being an open system of competition in which whoever can solve a problem will organically rise to the top, that is a theory. That's putting it politely. But there is a reality that is at odds with that theory, and that reality is that a lot of wealth, a lot of power, has been hoarded over centuries of oppression, centuries of exploitation, centuries of genocide pushing populations around. I give a very interesting example of the history of what we now know as Ghana, once British Ghana. Not only were enslaved Africans exported to that part of the world, but then indentured, I think, Indian workers were also exported. And this is throughout the churn of slavery, of the height of the transatlantic slave trade to post-slavery colonial situation to what is called independence and all of the trauma that came with it. I mean, trauma is an understatement. All of the sabotage and tragedy that came with it.

But that's just one example of how populations are moved across the world in service of capital, in service of production at the behest of a few people. A shockingly small minority of the world gets to decide how generations are going to live for centuries. So, the control of those processes, the control of who produces what and at what cost – that is tightly owned. And it's in that way, a handful, practically a handful of Western capitalists are able to influence trade policy. They're able to influence migration policy. The movement of not just people but capital. All of these things ultimately influence how a so-called democracy in the Global South will pan out.

HN: And there's one thing that you write a couple of times, that you think – and that almost happened once – that if African countries had a currency and they didn't have to trade in Western currencies, that would change things a lot. Why do you think that would change things so much?

GP: Currency is a big thing that it's just never really talked about in Western media. Never hear about what exactly it means to America to be able to control and create what is the de facto reserve currency of the world, the dollar.

HN: What does it mean for it to be like a reserve currency?

GP: Right. I'm just laughing because my editor Hugh’s in the room and he will remember how much I wrote on the start of the Central Bank and how much just never made the book. I've written chapters on this, but okay, so to be the reserve currency of the world, the dollar basically plays a function in which all currencies can be valued through the dollar. And this is from a long process of colonisation, Western colonisation of the Global South deciding where value would be transferred out of the Global South into the imperial North, and deciding that, ultimately, because wealth passes through our hands and we are the controllers of industry, our currency is more valuable than anyone else's because we know we effectively call the shots. So, having the dollar as the currency that defines the value of other currencies puts America in an immensely powerful position.

There was once a French minister that called it an exorbitant privilege. Funny that I just mentioned a French minister, because France has done the same thing in Central and Western Africa. Through France's control of these Central and Western African currencies, they get to define relative to France's currency, which is now the Euro, they get to define the monetary policy of these countries. So that translates to a pernicious power dynamic, an undemocratic power dynamic that, ultimately, shapes the options of these countries.

And we never talk about it. It is presented to us as a force of nature: “Of course these currencies are superior. Of course those currencies are inferior. Because implicitly these guys are kind of inferior. They haven't caught up. They can't do capitalism as well as we can do it because, hey, we're not gonna pass judgment, but they just don't seem to be able to be honest and hardworking enough to really come to terms with our capitalist system.” There's no debate about this in most economic classes at the start, at the outset of most economic courses. This is not interrogated. It's just the starting point of our economic analysis. But built into that are so many damaging restrictions on the options that many countries have in the Global South for the purpose of building prosperity and exercising political freedom. It's just not an option for them.

HN: And in this book, you look at the broader context. You're looking at things globally, you're also looking at things personally, and there's a conflict that you write that you have, which is the kind of making those something-is-better-than-nothing changes that work within the system versus making radical changes that will change your system or work outside the system. How are you doing with kind of balancing those two things and deciding where to put your energy?

GP: I think a lot of it is about ego. It's an ego battle. It hurts to think of yourself as someone who is part of something problematic, or to think of yourself as someone who is dependent on inequality, dependent on injustice. In order for us to continue to wear nice clothes and to have trinkets and conveniences in this world, we rely on the continued extraction of resources in places, parts of the world that are under the yoke of imperialism, like immensely poor – impoverished, I should say, not poor. Made to live in conditions of poverty. We don't realise how much of our security in the West is tied up – and when I say security, I mean, for want of a better word, I think our normalcy. Our sense that everything is ticking along fine is predicated on the ongoing violation, degradation – I don't like the word dehumanisation because it wrongly implies that any group of humans has the ability to make another group less human. All you can do is delude yourself that there's other groups less human, so you kind of dehumanise yourself, I guess.

But a lot of what we experience is based on that, and coming to terms with that is the big challenge. For those of us who were not born in a context in which this information is available before, we're old enough to just read it for ourselves and to watch the patterns of the world, so we tend to find out about this stuff as adults, by which time we are not trained in revolution. We are not trained in community organizing and political organizing. So, we end up conflicted, deeply conflicted about our role in the world, as am I. I think those of us in that position have to do two things. We have to continue to survive, and we have to find ways of surviving that are less and less harmful to the rest of the world. That's a challenge.

HN: And what would you say, if we're talking radical solutions, what do radical solutions look like?

GP: People talk a lot about dismantling capitalism, and I guess that's the most radical solution. Many people struggle with that wording because they get the image of something quick and intense and violent happening, some kind of 1917-style overthrow uprising. It wouldn't work in that way because of our militarised context, because of our digitised context as well. But there can be a gradual movement towards something else, which is why I write about socialism.

Now, I am not a specialist in socialist theory. I am not well-versed in so many aspects of what has been written for over a century now about the transition out of capitalism. I'm just reporting what I've become aware of over the past 10 years. Many people are working towards an economic system that is conscious, that learns all the lessons of capitalism, that is conscious that, yeah, capitalism was supposed to be a movement on from whatever came before, an era in which an aristocracy, a gentry, a monarchy tightly controlled things, into a new era in which control was expanded a little bit to what we now know as capitalists, as well as the aristocracy and gentry and monarchy, to now needing something after that to where control is expanded to everyone. I think it will take a long time of ensuring that a larger proportion of the world understands that trajectory, understands what capitalism is, how it started and how it's going. That is essential in my eyes, to gradually building the momentum and building the consensus for the next thing.

HN: And to bring it back to the music side of it, you write about Tupac and how he is a rare example of Black radicalism and Black music coming together. Do you think that there is a space in the current music industry for more people like him to emerge?

GP: I think the music industry is inherently anti that. In the case of Tupac, some days I think of him as an almost-revolutionary. Most conscious rappers, most rappers with any element of radical sentiment, I see them as almost; we probably wouldn't know them if they were fully. So, Tupac was successfully derailed, was drawn into conflict. And there is significant reason to believe that there was state collusion to intervene in his success and to potentially end his life. That seemed supported by the ongoing inability to pinpoint exactly what happened in the most famous strip in the world, the Vegas strip, on the night of his death. So yeah, Tupac is a kind of a flagship artist when it comes to radicalism and revolutionary sentiment in rap music. But you just won't hear the rest. There are a lot of radical artists.

I was explaining this point to someone about Kendrick Lamar the other day. I don't perceive Kendrick as particularly radical, radical at all, but someone was saying that he's one of one. And I was trying to say that I believe that to be a manufactured narrative. I know loads of rappers and poets who are very talented, whose politics is much clearer than mine, and who are deeply rooted and committed to their community, but the mainstream will never know them because, as I said at the start, the industry is against that kind of politics. So yeah, the expansion of control, again, the expansion of control to everyday people in terms of Black music with regards to what we create, how we address our problems, how we talk about ourselves, that has to be taken away from the music industry in order for radical politics to reach its potential.

HN: We've talked about how this book was a long time in the making. When you sat down to narrate the audiobook for this, what was that like?

GP: I didn't sit down [laughs]

HN: When you stood up [laughs].

GP: When I stood up, yeah. The audiobook was an amazing process, because I got to read my words out loud back to myself. I hadn't done that. You know, you don't realise that you read internally. So the audio thing has become so important to my career. I ended up making a podcast in which, again, I am talking myself initially through a lot of the stuff I'm learning, but I'm doing so in a way that is accessible to my audience. That's what I do in the audio form. And recording the audiobook was another very cathartic extension of that process.

HN: Well, George, it's been such a pleasure to chat. There's a million things I could pick up from the book to chat to you all day, but I will leave it there and people can go and have a listen.

GP: Listen, man, thank you very much for a very fair conversation. I didn't know, talking like this on such a public platform, but I appreciate it.

HN: Thank you. Thanks for listening to Audible Sessions. If you enjoyed this and want to hear more, search Audible Sessions on the Audible website or on the app. Track Record, written and narrated by George the Poet, published by Hodder & Stoughton, is available to listen to on Audible now.