Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

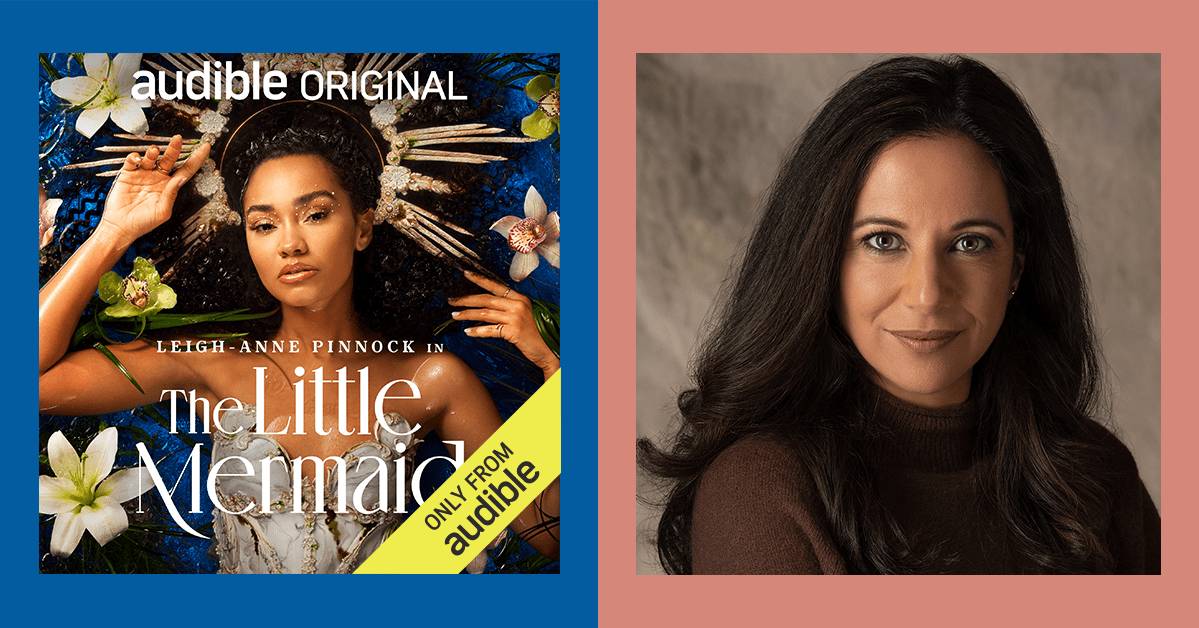

Emily Cox: Hi, I'm Emily, an editor here at Audible, and I'm so thrilled to be speaking with Dina Gregory, the author behind the new Audible Original adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's classic fairy tale The Little Mermaid, performed by Leigh-Anne Pinnock. Welcome, Dina.

Dina Gregory: Thank you, happy to be here.

EC: It's so great to have you, and I feel like I just need to say for those listening in that Dina and I are old, dear friends, so I am super excited to have you here to speak to you in a professional capacity. It's so exciting for me to get to experience your talent in this kind of way, and to really experience your creative work outside of knowing you personally. It's really cool.

DG: It makes it extra, extra special for me too. I remember talking to you about stories long ago on those trails in South Orange, and now here we are, here are the stories.

EC: Here we are.

DG: It's really neat.

EC: I can't wait for our listeners to experience The Little Mermaid. I only just first listened to it last week. I thought it was absolutely marvelous. I'd had a little bit of a preview of the script, but listening to it just put it in a whole different space for me. What did you think of the production when you got to listen to it?

DG: Oh, my goodness. Well, I'd been living with this story for over a year now, from conceiving the way I was going to adapt it, and then those first meetings. So, it's over a year of it being just in my mind. And then I, like you, only heard it a couple days ago. And oh, it blew me away. It reminded me of that excitement I feel when—so, I write musicals as well as stories, and I write songs. And I often, I'll send a lyric to my sister, and that first moment where I hear how she set the lyric is just a really special moment, when you realize that people have got your vision. And in that case, it's my twin, but in this case, it's a whole team of people who brought this concept to life. And I instantly knew when I was listening that we were all sharing the same vision. So that's a really kind of special feeling, and I was so excited.

EC: That's so cool, yeah, when you're like, "Oh, wow. They got it. They picked it up in the right way." I am going to listen to it with my kids—I haven't yet—but I'm going to have to caveat for them that it's quite different than the Disney version that we all know and love as well. You've really stuck a bit closer to that original, darker version of the tale.

DG: Yeah. We definitely at the start of this wanted to share something closer to the original Hans Christian Andersen story, which was written in 1837, a long time ago. As you say, it's different. It is darker. It's not the happy-ever-after fairy tale that we've come to think of The Little Mermaid as. And, yeah, I did a lot of thinking about why we tell that now, and I do think there are good reasons to try and do that, especially the sort of climate that kids are living in right now. It's messy, it's complex, there's some really big things going on. There's climate change, and we just had the pandemic. I think there's something about telling stories that kind of reflect the messiness of life and gives kids a chance to explore that through a controlled world of fairy tale that can help you with your real life and equip you.

"When children get to go up against fairy tale monsters, it gives them confidence and the tools in their own real-life challenges."

I'm sort of saying something that psychologists—I think it's Bruno Bettelheim who first posited that theory, that when children get to go up against fairy tale monsters, it gives them confidence and the tools in their own real-life challenges. So, I was buoyed by that idea, and thought, "Yeah, we should tell something closer to the original fairy tale. It would be a gift, I think, in some ways, for kids now.”

EC: Yeah. That's interesting. So many fairy tales did start off as quite dark, and then they've gotten a facelift, there's a little cosmetic change to make them a bit more palatable. Do you think it's important that we start leaning into the darker side of fairy tales again? I guess we see that with some of the more recent retellings in movies anyway, and dystopia, and things like that.

DG: Yeah. Even Marvel, there's more of an embracing of some of the shades of gray. With that being said, I wanted to do this in a responsible way. I came up with a conceit for this adaptation that I hope makes children feel safe as they go through the story. The narrator is directly talking to them. She's using direct address and speaks to them in their rooms with their Bluetooth speakers and their headphones. And she's saying, "Okay, this next bit might be a little bit upsetting, but, you know, bear with me." She's able to sort of guide them through it, while also speaking the language of this darker version. And she even says, "I've seen you face your own challenges. I think I can trust that you can handle this." I wanted not for it to feel like a solo journey, but to feel like they had company.

EC: Yeah, I really felt like she was almost a docent taking me through something, holding my hand and letting me know that it would be okay. And I thought that was a really unique touch. The narrative voice in general, I mean, that's something else I thought was cool. While the story might have been closer to the original from the 1800s, the voice was quite modern. How did you land on that type of real contemporary sounding voice?

DG: The narrator really opened this up for me. I’m a character writer. I write through character, and so deciding who would tell the story was a big choice. At the end of the original fairy tale, Hans Christian Andersen references these sylphs, or daughters of the air, who live for centuries. It's part of the way he wraps up the story. And I don't want to give too much away, so I'm going to try and dance around certain things, but I chose to have the narration be delivered by a sylph, by a daughter of the air who lived then, when events unfolded, and is here now. It's like a mystical creature. So, she's witnessed changes, she's seen the world change, and so she's able to acknowledge where we are now. She says things like, "I see how your air waves pulse with information, but I mean to use those waves to conjure others," meaning to bring them beneath the sea and conjure this undersea world. That was key for me, in “How do I take this fairy tale written in 1837 and bring it to 2023?” I don't want kids to feel like it's inaccessible. I want them to see the resonances and the themes. There are some themes that really speak to now, which I'm sure we'll get to.

EC: I wanted to ask, what do you feel was important to keep and drop from the original story?

DG: Since it was written in the 19th century, there's a bit of a fusty Victorian moralizing feel to the ending. But also there's some undertones, there's a theme in there of redemption through sacrifice—

EC: Which would have really appealed to the Victorians, right?

DG: Exactly. But maybe not so much now. But what there is also in there is knowledge through sacrifice. The Little Mermaid is seduced by this other reality. She peers up above the water and she sees the human world, and she's so seduced by that world. She wants to know what it feels like, what it would be like to be there. And that seduction of other realities is something we are living with right now, with social media, with all our feeds.

EC: Oh, yeah.

DG: We see these other worlds, we see our heroes, our heroines, and we kind of want to be like them. We want to know what that's like, we want to feel what that's like. And the Little Mermaid's journey, we see how when she experiences that reality, especially in the original fairy tale, it's mixed—there's some dark elements and there's some joy to it as well. But she grows stronger through that journey, even though she gives up her voice to get there, to get to the human realm.

EC: Interesting when you compare it to social media. Suddenly I'm like, "Oh, God. We do give up our authentic voice to engage in other places." That hadn't sort of landed for me. That's really fascinating to think about.

DG: And this notion of sacrifice. I'm definitely a sucker for stories with sacrifice. I mean, thinking of C.S. Lewis and Aslan. But usually when you're pursuing knowledge, there is an element of sacrifice. My mind is going to who narrates this, which is Leigh-Anne Pinnock. Her dream was to sing, to be a pop star. So she had to sacrifice the safety of her home and the comfort in what she knew and the ordinary world, and go to this level of pop stardom, superstardom. And then she discovered the truth of the pop world and all its different colors. And I think that's what's neat about this and her narrating, is that I was able to emphasize those parallels, which are really there, you know? She then used her experiences, and I think she found that the pop world is not always hospitable to women of color, or at least the industry and the fan base can, at times, be inhospitable, and she used that experience; she grew stronger from it. And she's used it to share her story and empower other people. I just see so much resonating with the Little Mermaid's journey, which has been a real joy to bring out and emphasize.

"The Little Mermaid is seduced by this other reality... and that seduction of other realities is something we are living with right now, with social media, with all our feeds."

EC: It felt like a real perfect casting in that way. So, Leigh-Anne Pinnock is probably newer to the US audience. What can you tell us about her?

DG: So, Leigh-Anne rose to fame in this British girl band called Little Mix, and they had hit after hit in the UK. And now I think they're considered one of the most successful girl bands of all time. They've sold something crazy like 60 million records worldwide. So, in the UK, she's super well-known. And on a personal note, when my nephew, who lives in the UK, heard that I was doing this—he's a big fan, and he's seen them perform live—I definitely got cool aunty points when he learned that I was doing this.

EC: [Laughs] Well, I really loved her voice. It was just so, I don’t know, authentic, or real.

DG: Oh yeah, I loved the way she read it. I felt like she really connected to it in just a lovely, expressive way. And she sort of brought a lightness to what can be quite a scary and mysterious tale, and I just really liked what she did, the way she read it.

EC: Yeah, she really owned it, she owned that character. It was good.

DG: Yeah. It's so perfect to have somebody who is so famous for her beautiful, gorgeous singing voice telling the story of a mermaid, who was meant to be, in the mer-kingdom, famous for her beautiful singing voice. So, there's that lovely synergy there.

EC: So, I wanted to dig in a little bit more to this—I mean, you've talked about how she was seduced by this other realm. But I feel like there's something that certainly was true in your story as well as the Disney version we all know—that love-at-first-sight moment, which I think is still there in both of them. But in your story, it really evolves into this sort of love of humanity. Is that something that's present in the original story, or is that something that you brought in?

DG: I think I leaned into this idea that she didn't just fall in love with a prince, she fell in love with the world, and that world fused with the prince. I was very aware that for some kids, this is a first-love story, which is a beautiful kind of love. That first love is so tender and confusing, and I think you can often mistake your feelings for a person with your feelings for whatever realm they inhabit, or whatever—

EC: —moment in life you're in.

DG: Yeah. I call it a strange alchemy. It's kind of mysterious. But the reason I wanted to emphasize that is because the original fairy tale, you could read it as she just falls in love with a prince and then she uses her looks to charm him into marrying her. That's not very empowering. But it's really that she falls in love with a prince, definitely, but she also falls in love with the idea of him and with the idea of what it's like to be on land and to ride through the trees and have all these adventures. She's mixing it all together, and it's merging and it's creating this really potent desire to get there and to figure out how to meet him.

I like to stay authentic to the original writing, and so I took things that were in there. For example, Hans Christian Andersen mentions when she does her deal with the witch and gives up her voice, gets legs, she goes onto land and she's beautiful, and she has all these beautiful dresses given to her, but she also gets the suit of a page.

EC: What does he call her? What's that word?

DG: Oh, my foundling.

EC: Foundling. Interesting, yeah.

DG: I know. Again, it rings a little differently, but what I tried to emphasize is that that suit that she got was her favorite because it unlocked the world to her, and the secrets of the world. She was able to go riding with him, do all these active things. She wasn't just using her looks. It was her spirit that he was drawn to, and it was that spirit of curiosity that drew her there in the first place.

So, in some ways, that's modernizing it. It's like an awareness of where we are, and I'm sure a Victorian male was more comfortable with the idea of, A), that the human world is implicitly better than the mermaid world, and, B), that her love for this man would be enough. But the seeds of other things are in there. All I was looking for is permission to expand on certain aspects and deemphasize others.

EC: I wanted to talk about mermaids a little bit. I feel like there's been a few mermaid stories coming out recently, and there's a debut novel that's out this year called American Mermaid. We actually just spoke to that author. In [that] conversation, they reference the Hans Christian Andersen tale and noted that mermaids have kind of historically and inherently been tied to the male gaze in some way. You know, it's sort of weird if you think about it. Fish tails shouldn't really be sexy, right?

DG: [Laughs] Right.

EC: But what is it about mermaids that have fascinated us? Your story definitely ends on—it's got a feminist aspect to it that is interesting, and does sort of lift it up and out of where Hans Christian Andersen would have been thinking about mermaids.

"It's so perfect to have somebody who is so famous for her beautiful, gorgeous singing voice telling the story of a mermaid, who was meant to be, in the mer-kingdom, famous for her beautiful singing voice."

DG: Right. Well, you're totally right. I mean, it must come from Greek mythology, and the whole siren mythology and this idea of mermaids calling sailors to their death.

EC: Which comes out in your story a little bit too.

DG: It does, and I'm drawing from the original fairy tale, and perhaps I make more of it than even Hans Christian Andersen did, because he references the sisters of the Little Mermaid and how they at first seem delighted to go up above the water to look at humans, but they tire of it, and then they start wanting to possess what's up there and bring it back down. But I saw that as my opportunity to differentiate the Little Mermaid from her sisters. So, one of the other themes in this story, which is beautiful, I think, is her kindness, her large heart. And so for me, that was an opportunity to emphasize that contrast, and to show that she wasn't like her sisters. She had an intellectual curiosity to know, she wanted to go beyond her world and know more.

It's that that I wanted to emphasize, and this story is what it is, but I also think “What would be the Little Mermaid's opinion on her own journey afterwards?” Again, I don't want to give too much away, but through the way that I tell the story, I allow listeners to think about that, and to say “looks are not enough on their own.” And look, giving up your voice is not okay. Would the Little Mermaid regret her choice? Maybe not, because she grew from the experience, and was able to share her story. We tell her story over and over in all these lovely different forms, and in some ways, she's gained immortality through that story, the kind of resonance there.

EC: There is a real sort of meta-ness to it, yeah.

DG: But I'm saying take heed from this fairy tale, because to be truly loved, you have to be known, and I think that that was a message I wanted to put in there, because I wanted to speak to people now.

EC: She was sort of lifting herself out of the stereotypes of even what women on land had to face, right? She really loved being able to be his partner.

DG: Yeah. And maybe her being other, being formerly a mermaid, that the rules of the human world were confusing to her, and so she was, "Of course, why wouldn't I jump on the horse and ride with him?" And maybe for a royal in that time, that was refreshing, somebody who's not confined by the expectations of the time. And so, yeah, having no voice is a huge thing, obviously, but I think that it was fun to emphasize these other aspects of what might have connected them. And I say the original fairy tale doesn't necessarily have in the cards that there's a happy-ever-after ending, so there may not be wedding bells. So, there is a different message to be had from the original.

EC: Yeah. I'll never forget watching the Cinderella live-action movie with [my daughter] Cece when she was three or four, and at the end scene when you see her in a wedding dress, Cece looked at me and said, "I want to get married." And I was like, "Hold your horses." And I think that there has to be a different message than just, "I want to get married." As much as I love a happily ever after as much as anyone.

DG: Yes, and I have nothing against the Disney version. I think there's a time and a place for everything, and I love when stories live on, so I'm all for that. But it's funny, you're talking about Cece’s response, my daughter Soraya’s response was, she overheard me reading out my adaptation along the way, and she's like, "I would not do that. I would not give up my voice. I would not want legs if it meant that it felt like walking on knives with every step." She was so full of what she would not do, and I thought, "Great. You know, this is kind of what someone like Bruno Bettelheim was saying.” It helps kids clarify where they stand on things, how they feel about things, and I would much rather be sending the message “Think carefully about what you're willing to give up for love,” rather than just “Give up everything and you'll get your prince,” you know?

EC: Right. Absolutely. I feel like we are dancing around the ending, and I don't want to spoil anything. So, I want to ask you about other fairy tales. What else do you think needs to be revisited, or what would you love to see resurrected in its original form?

DG: Ooh, that's a great question. I'm thinking about some of my favorites, like Rumpelstiltskin. One of my real favorites, it was really short, it was a picture book on my shelf growing up: Teeny-Tiny and the Witch Woman. I think it's based on a Turkish folklore story. But I love stories that have portals to other worlds, so that you step through and suddenly danger and magic are prevalent. I would love to try my hand at one of those types of fairy tales.

But it's funny, the fact that you're saying that there's been a lot of underwater mermaid things recently. I think that the time that Hans Christian Andersen was writing, they were only just exploring the ocean, so they were getting the first images of what was under there. I think that was so new at the time. What I think is neat is sometimes with these fairy tales, you can modernize them in really interesting ways. So, we obviously now can see underwater with an amazingly beautiful view in these documentaries. I mean, you can't get better underwater cameras, and you feel like you're down there. So, I was able to sew in a little bit more of what we know now in some of his underwater descriptions.

Like, we know about bioluminescence. They wouldn't have known that then. So when I was describing the ball, I was talking about these iridescent sea stars. When the Little Mermaid goes to visit the witch, it was a little confusing in the original; he almost makes it seem like the witch is above water. She calls it her swamp, and some of the descriptions are confusing. You're like, "Am I still under the sea or not?" I think Disney and I both chose to keep it very much clear that she's underwater. But we now know about these underwater vents with volcanic springs, and so I could describe that as the reason for it being hot and bubbly. And so it's kind of fun to take what he knew of the underwater world, that first love of the ocean, of what's under the ocean, deep under the ocean, and to fuse it with what we know now, and in that way, sort of update it a little bit.

EC: You think about in the 1800s and even earlier, so many parts of the Earth were undiscovered to Western writers. If you think about, like, Candide, the way that that story unfolds feels like science fiction, even though it all took place on Earth, you know? I think that parts of the world were so undiscovered to people who hailed from Europe that a lot of those stories feel like science fiction because they're so fantastical.

DG: But I think that some of the freshness—like when I was working on this adaptation, I just loved the prose, and some of the descriptions were because it's fresh, because it's that first thinking and imagining, and it's probably what made it so popular initially. It's a whole world that people were not thinking of and living with, so it gave it, like you say, that sort of science fiction feel, probably from the get-go.

EC: Yeah, like [20,000] Leagues Under the Sea, that sort of thing.

DG: Oh, yeah, same era, wasn't it?

EC: Yeah, it sort of sparked everyone's imagination. That's interesting. You've done another major adaptation for Audible recently. Last year, you did The Wind in the Willows, and it was voiced by four amazing female voices. How much liberty do you think you can take when you're reworking a classic?

DG: I think you can take a lot of liberties. I think you must always stay true to the original spirit. What's beautiful about Wind in the Willows is the relationship between those anthropomorphized animals. It is so charming and whimsical, and so I think you can't go against some of what makes a piece of work essential and beautiful and timeless. But if your goal is to reach new ears with something beautiful, then I think that that's a good goal.

"Take heed from this fairy tale, because to be truly loved, you have to be known, and I think that that was a message I wanted to put in there, because I wanted to speak to people now."

I'm thinking about the books I loved growing up. Nearly all of them, the heroes were males and the wicked characters were females. And so I'm worried that kids now and parents now will be looking for the stories that don't necessarily conform to that, so they might get more restricted to modern fiction and recent publications, where we're doing a great job now of having more diverse characters and having female heroines. But I don't want us to lose our rich literary heritage. So, if there's a way I can bring some of these stories I loved into more kid's hands—I think I even say it in the beginning of my Wind in the Willows adaptation, that one of the characters says, "Well, if they don't like this, they've always got that other version." It's like they say, the original is always there. For anyone who wants it, the original is always there, and if what I've done has made you so frustrated that you want to go to the original, that's a win too.

EC: That's great too.

DG: Anything to keep the stories alive.

EC: We've been adapting stories forever, right? They are clay, and they keep getting passed along the generations.

DG: And for each age, something else will feel most relevant. For Disney's adaptation of The Little Mermaid, that really hit the spot in, what was it, the '80s?

EC: Yeah. I think '89-ish.

DG: Who knows what the next incarnation of that will bring out, but I'm sure they will try to emphasize something just a little different, as I've tried to emphasize things that I value for kids now.

EC: You mentioned that you have written for theater and musicals. How does your background in that inform your approach when you're just writing for audio, without the visual elements?

DG: I'd say it has a really big influence, actually. You train yourself when you're writing musicals to leave room for the music, leave room for the songs. So when you're writing a book scene, you hold back from the emotions so that the song will take over and express the emotion. And in the song, you don't overwrite the lyrics because you trust that the music is going to flesh that out. So I think I bring that to oral storytelling, to Audible stories, because I leave room for what I know they're going to be able to create after my words. And, boy, did they do it this time. I mean, it's been a thrill to see. I think, for example, I have a line in there where the narrator says, "And plus, I have music on my side." And I didn't explain what she meant by that, I just trusted that music would be there; it would fill in that line.

EC: And it does, it swells so much.

DG: I feel like this production, especially, is the absolute cutting edge of technology, and I gave them room to bring surround sound and that 3D immersive experience. I didn't need to use all of the original fairy tale. There's the temptation to be so reverent with an original fairy tale that you want to preserve lots of it. But I think, well, two things: I think our attention spans are different now than they used to be, and so I wanted to abridge it, but I also trusted that what I cut out—the descriptions, the lovely descriptions of the other sisters’ journeys and things—that would be filled in by the music and the sound. And Joe Wilkinson did the music for this, and it's totally the element that I was hoping would be brought in. So, yeah, I think musical theater writing and this kind of storytelling are actually very synergistic.

EC: That's really cool, the idea of leaving space for that music. That comes across here. It's so good. You've written these two awesome adaptations for Audible, but you also have done quite a few really sort of micro short stories for audio, and I just love them, my kids love them, we've listened to all of them. But I wanted to ask you, what's your favorite, if you had a recommended one?

DG: Oh, I'm so pleased you're asking me about these because I love writing them. I love writing original stories as well as adaptations. And let's see, my favorite, it's probably a story called the “The Pelbunkin.” And it's based on a game I played with my son when he was little and I was bathing him, and we would have these foam letters and spread them on the edge of the bathtub and make up these nonsense words, and then he would listen as I made up a story about the nonsense word. And so that's how that story was born, “The Pelbunkin.” It's a little frightening, but not too frightening, I hope.

EC: No, it's really good. All right, well thank you so much. It was so great talking to you. I loved hearing about all of the underlying themes that you really were playing with, and I can't encourage our listeners enough to pick this one up. The Little Mermaid. It's really special, so enjoy.

DG: Thank you so much.

EC: Thank you for being here.

DG: This was so fun to talk stories, my favorite things in the world.

EC: It was great, thank you. And listeners, you can get The Little Mermaid now on Audible.