What makes a good book title? It’s the question that writers and publishers have pondered for centuries and nobody seems to have come up with a conclusive formula as yet. We all know a ‘good’ book title when we see one, and we also have an inherent sense of a ‘bad’ book title, but putting your finger on exactly why something goes into each of those categories is tough.

Things have changed since the advent of the internet. Creating something that looks good on a bookshelf is very different to something that’s going to catch the user’s eye when scrolling through a list on their phone.

In this increasingly competitive world, grabbing the attention of potential customers with your book title is the difference between it being read or left languishing. Should you incorporate an alliteration or spoonerism? Is there a correct configuration and number of nouns? Should you be literal or keep it abstract?

Let’s see if we can navigate through this minefield of a topic.

How influential are book titles?

Is it really that important what goes on the front cover of a book? Surely it’s the words inside that are important, especially now that people are just as likely to be listening to an audiobook or having the anonymity of an e-reader rather than having their guilty pleasure on show to the rest of the train carriage.

But it does matter. A lot. It’s arguably the most important marketing decision you’ll make and one that can make or break sales. The book market is a busy one, and consumers have a habit of making a snap judgement on whether or not a book is for them. Dull title? No, thanks. Clichéd title? I’ll pass. Convoluted title? Next, please.

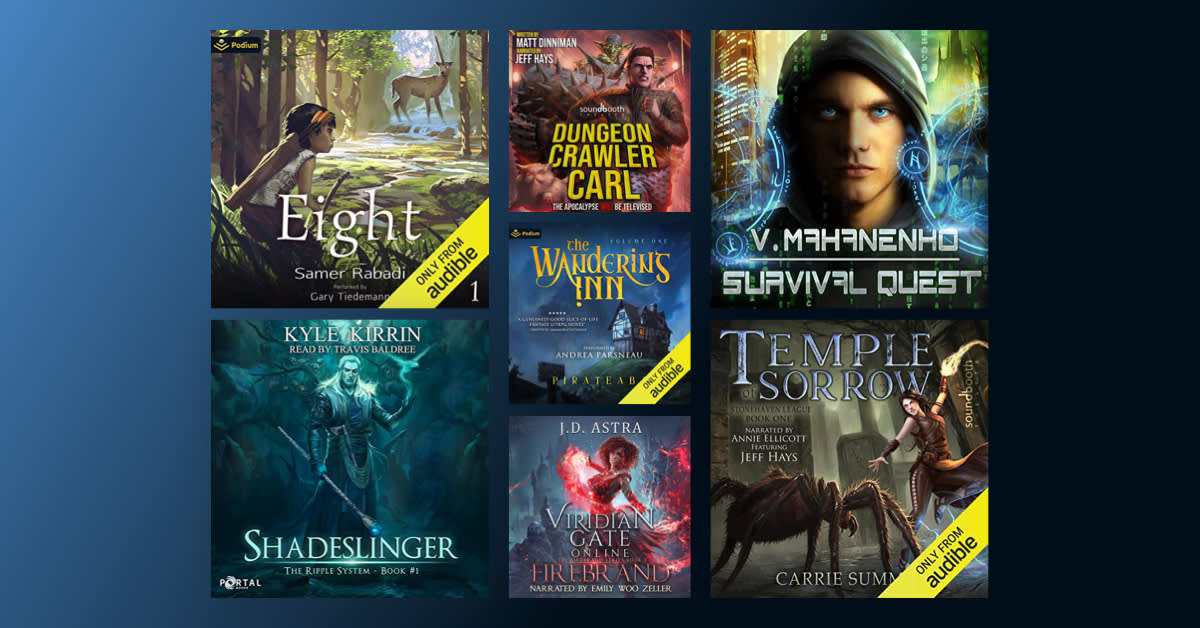

This brutal reality is true for both online and in-store browsing. Grabbing someone’s attention is difficult, and there are some tough titles to compete with to make someone stop scrolling. Titles like:

All My Friends Are Dead

Are You There, Vodka? It’s Me, Chelsea

And that’s just the A’s! There are thousands more examples before you reach Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

How to find a unique book title

Analysis by tor.com of the most popular fantasy and science fiction published between 2000-2010 found that the most common words in titles were:

Shadow

Dragon

War

Night

Dead

City

Dark

Blood

Magic

World

Hit the randomise button and there’s a pretty good book title in there – would you buy a copy of Dark Blood City: The Shadow Dragon War?

There are only so many words in the English language and, as with all the best website addresses, there’s a good chance that the best ones have already been taken. When we say ‘taken’, that’s more in the sense of ‘used’ rather than ‘reserved and now out of bounds’. You can’t trademark an individual book title. However, the law is more definitive when it comes to a series of books. Once a few books have been released under the same name, this becomes a ‘brand’, which can be trademarked in the same way as any other commercial product.

There’s a temptation to ignore what’s come before and have faith that your book title will stand tall amongst the rest. However, if you want people to find your book, at some point you’re going to have to rely on Google, and getting them to recognise the greatness of your book against all others is about far more than it being the best in its class.

And it’s not just works of literature that are going to cause an issue either. Take Gathering Storm, for example. It’s a good title for a book and one that Winston Churchill decided on for his memoirs (which have inspired two movies and a TV drama series), as did the authors of a 2007 fantasy novel, a 2004 video game, a whitepaper from UNICEF and countless other published works.

So, good luck with getting your book of the same name any traffic from a search engine.

Using shock tactics in your book title

There’s been a recent trend in sweary book titles in an effort to make the audience sit up and take notice. The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fck*, Go the Fck to Sleep*, Sht My Dad Says* and countless others, most often found in the self-help section.

Swearing hasn’t always been perceived as vulgar in society. The Romans used to shout out rude words in the middle of weddings to promote fertility. In the Middle Ages, many of today’s swear words were not seen as remotely obscene (hence some of the interesting street and town names scattered across Britain).

Something changed around the time of the Industrial Revolution, when bodily functions went from a daily occurrence on the street to the comfort of your own home. When going to the toilet in full public view went away, so did public acceptance of swear words.

500 years later and modern science tells us that swearing has several benefits to humans, from making us more persuasive to promoting trust and teamwork. Using vivid and figurative language elicits a range of emotions, which then provokes the brain’s decision-making centre and makes something more memorable.

How do we translate all those signals we’re getting from the brain in a consumer context? Simple: “I must buy this product”.

It’s no surprise then that authors have harnessed this power. In Steven Pressfield’s 2016 book Nobody Wants to Read Your Sht*, he explains that it’s important to have a concept in your writing that attracts readers and keeps them engaged. Something provocative that transforms a boring product into something truly memorable. What better shortcut to this end goal than throwing in a liberal quantity of S- and F-bombs?

Using a sweary title for your new book isn’t always a quick win, though. There is a generational divide to take into account. Research shows that older readers find this style of writing a turn-off, so this is primarily a strategy for thirtysomethings and younger readers.

Authors may also run into issues with book promotion services who won’t accept swear words in a title, or add an ‘explicit’ tag which will make it invisible to some of your audience. Facebook will not let you run an ad using any kind of obscene words and promotional emails could even get filtered into the Spam pile.

So, while publishers don’t have any official rules against swearing, it’s clear that some are still clearly intimidated by this language.

Who decides on a book title?

For some authors, the title for a book comes way before they actually start writing out the storyline. In those instances, they become firmly wedded to what their book will be called, and will be somewhat taken aback when a publisher rubbishes the idea and sticks something entirely different on the cover.

In the same way that newspaper journalists will hand over the responsibility to headline writers for the large-font words that will appear on the front page, authors shouldn’t feel downhearted when their book gets released with a different name than the one they’d envisaged.

Ultimately, it’s a different skill and, while you may be able to crank out 100,000 beautifully constructed words for your crime novel, you may not be the best at choosing the four words that will help get it marketed to millions.

That’s what the publisher is there for, and there’s a lot to be said for their experience.

Ultimately, it needs to be a mutual decision. The publisher can dig their heels in and refuse to release the book if the author isn’t flexible and, likewise, the author can take their book elsewhere if they don’t like the way their pride and joy is being presented.

But most of these standoffs can be overcome and, like any good relationship, a healthy argument can often help things prosper.

What books were almost called

Have you ever had that feeling when you thought you knew something, but actually your whole life has been a lie? Turns out a lot of those books that you loved like your own family haven’t always been who you think they are. Would a rose by any other name have smelt as sweet?

Take The Great Gatsby. Poor F. Scott Fitzgerald went through about seven different titles including Trimalchio in West Egg, Among Ash-Heaps and Millionaires and The High Bouncing Love, before he begrudgingly settled on the one that has become so well known.

One of the titles Bram Stoker considered before settling on Dracula was The Dead Un-Dead, which is arguably the far better title, but perhaps not one that would have entered folklore with such significance.

And beloved author Jane Austen must have been having an uninspiring day when she thought the title First Impressions would be a suitable follow-up to her debut novel Sense and Sensibility. Fortunately, author Margaret Holford had just published her own First Impressions, leading Jane down the path of the now iconic Pride and Prejudice.

Books that become TV shows or movies will often change their names along with the change in format.

Remember that huge TV show A Song of Fire and Ice that everyone on the planet obsesses over? No? You’ll probably know it better as Game of Thrones, which is a far more accurate title for the tale of a bloodthirsty race to power.

Everybody’s favourite Christmas movie Die Hard was originally Nothing Lasts Forever on the bookshelves. Screenwriters Jeb Stuart and Steven E. de Souza made a number of right calls when they adapted the book, including the name change and a very different ending. We won’t give any spoilers away but, if you haven’t read the original, it’s worth checking out what Jon McClaine’s fate could have been.

Books can also have different titles when they cross international borders. Some simply don’t translate well into other languages, whereas some are simply seen as more marketable under a different name. Harry Potter fans visiting the US may be excited to see a seemingly new book called The Sorcerer's Stone. However, they’ll quickly see that it’s the exact same Philosopher's Stone that was published back home.

Wikipedia lists hundreds of these transatlantic differences, including examples like The Iron Giant by Ted Hughes, which changed its name to avoid trademark infringement with a certain comic book character.

What’s the ideal book title length?

Another of those unanswerable questions. Who’s to say the single-word Twilight is any better or worse than the comparatively lengthy The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe or The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest?

Perhaps as a result of the increasing volume at which titles are being released or the prevalence of sequels, there is a growing trend for longer titles. Research from towardsdatascience.com on books released since 2011 found that the average number of words in a title went up from around 2.5 words and 12 letters to almost 3 words and 14 letters.

This is by no means a target or a magic formula, but it is a guide to base some of your options around.

Hopefully, you’ll be in a position to be saying your book title over and over again in interviews, at lectures and at media appearances. The best title is the one that matches the essence of the book, that is succinct with its syllables and is memorable for your audience, so they can recommend it far and wide once they’ve finished it.